Poland: Presidential Election 2020 Scene-Setter

Poland: Presidential Election 2020 Scene-Setter

This is the third of a series of pieces the Observatory intends to publish on societies and elections at risk from online disinformation. Our goal is to draw the attention of the media, tech platforms and other academics to these risks and to provide a basic background that could be useful to those who wish to study the information environment in these areas.

Following the parliamentary elections of October 2019, Polish voters will return to the polls in May 2020 to elect a new president. Poland’s fractious domestic political environment and troubled relations with the European Union make it a likely target for malign influence operations. Indeed, Polish politics has been awash in recent years with troll farms, hyperpartisan media, conspiracy theories, and influence operations originating in Russia. Over the coming months the Stanford Internet Observatory will track influence operations in Poland and observe the online dynamics of key national and international actors with a stake in this important election.

Political context

Polish politics is dominated by the conflict between the governing Law and Justice [Prawo i Sprawiedliwość] party (PiS), which many observers consider right-wing populist, and the coalition of four parties opposed to it, led by the Civic Platform [Platforma Obywatelska] party (PO).

PiS has been the governing political party in Poland since 2015, when its candidate Andrzej Duda won the presidency and it racked up an absolute majority in the Sejm, the lower house of parliament. PiS achieved these gains thanks to the appeal of its particular combination of right-wing populism and left-wing economics, which included anti-immigrant and anti-LGBT rhetoric, overt nationalism, and redistributive measures, including the popular 500+ program, which provide assistance for low- and middle-income families. PiS has also positioned itself as an EU antagonist, and its policies and rhetoric have created constant friction with Brussels. Finally, the party has sought to entrench itself by using its majority to take control of public media and restructure Poland’s judicial system, triggering a series of constitutional crises. It was this last action, in particular, that led the European Commission to trigger Article 7, which could lead to sanctions and Poland’s being deprived of voting rights in the Commission.

PiS’s strong-arm tactics have been divisive, and its victories in the 2019 European Parliament and Polish Parliamentary elections took place against a backdrop of increased polarization in Poland. Indeed, while PiS was the clear victor in October’s elections, it lost its majority in the Senate, resulting in a divided legislature in which the opposition will be able to hold up legislation and thus impede some of PiS’s efforts to solidify its position. This has led some observers to point out that PiS might have “hit its ceiling.” Others have suggested that, given PiS’s promises to intensify (rather than moderate) its policies if rewarded at the polls, its victory might herald more democratic backsliding.

The process unfolding in Poland has international implications as well. PiS’s euroskepticism and the country’s repeated conflicts with the EU have made Poland’s course one of the key questions concerning the EU’s future. The EU will be watching the elections closely in the hopes of dealing with a more conciliatory Polish president. Likewise, Poland’s position as a bulwark of NATO in Eastern Europe makes it an important United States ally. While it is unlikely that Poland’s position vis-à-vis NATO will change, the US will be hoping for a reliable partner aligned with NATO’s other members and interests. Perhaps most important, Russia has a long-term interest in driving a wedge between Poland, a historical adversary and committed NATO member on its western border, and the EU and NATO. It has developed influence operations intended to isolate Poland as part of a larger “divide and rule” approach, and will almost certainly continue to exert itself in this direction.

Media Landscape

Traditional Media

In general, the media environment in Poland has become more polarized, fractured, and contentious since PiS came to power, with increasing levels of vitriol. Hostile actors and troublemakers—domestic and foreign alike—have taken advantage of these conditions to influence Polish politics and stoke tensions.

Polish newspapers and television networks have historically been dependent on advertising spending from state-controlled companies, and this makes them sensitive to the coverage needs of the current governing party, which tends to dole out advertising money to sympathetic outlets. PiS has expanded this channel of influence by significantly increasing ad spending by state-controlled companies and focusing this spending on a handful of favorable outlets.

PiS remains in control of Telewizja Polska [Polish Television, or TVP] which is the largest Polish television network and effectively a PiS mouthpiece. PiS also receives a considerable amount of positive coverage from newspapers which benefit from state-sponsored advertising, such as Gazeta Polska, wSieci, and Do Rzeczy, and is aligned with conservative broadcasters such as Radio Maryja (nationwide) or Radio Rodzina (local).

More or less aligned with the main opposition party PO [Platforma Obywatelska or Civic Platform] against PiS are the television network TVN, the daily Gazeta Wyborcza, the weeklies Newsweek Polska and Polityka, and two dominant radio stations, RMF FM and Radio ZET, as well as a number of popular websites such as Onet.pl, Interia.pl, and Gazeta.pl. However, this alignment is fluid, and more left-leaning outlets, such as Polityka and Newsweek Polska, can also criticize PO and the parties to its left.

A major bone of contention remains the question of foreign capital in the Polish media landscape. The PiS leadership has repeatedly called for “repolonizing” the country’s media, alleging that they are dominated by foreign (mostly German) companies that deliberately provide unfavorable coverage of the government. A number of broadcasters depend on non-Polish capital, e.g. TVN is owned by the U.S. media group Discovery, while others receive funding from Germany-based entities. The local newspaper market is likewise dominated by foreign, mostly German capital (e.g. Polska Press, part of Verlagsgruppe Passau, which owns more than 20 local newspapers). The fact that many Polish media outlets are foreign-owned brings together two political issues that are likely to feature in the election: allegations of “media bias” by PiS and its supporters can turn into allegations that the EU and its member states (especially Germany) seek to control Poland. On the other hand, PiS’s opponents can present PiS’s attacks on the press as more evidence of its hostility to free media and to the EU.

Social Media

Facebook is by far the most significant social-media platform in Poland, with almost 18.5 million active users, nearly half of the population. Trust in social networks as a news source is relatively high in Poland, and younger Poles in particular are likely to get their news from Facebook and other social-media platforms. Indeed, initial analysis of top Facebook Pages devoted to Polish politics suggests that engagement increases around elections:

Activity on partisan Polish Facebook Pages, suggesting a spike in politics-related activity on Facebook around the October parliamentary elections in 2015 (top) and 2019 (bottom). Courtesy of CrowdTangle.

Facebook is also the premier vector for domestic and international actors seeking to influence Polish politics, and the majority of disinformation campaigns that have been identified to date have used Facebook. We describe some of these operations in the Disinformation and Misinformation section below.

Relevant Facebook Groups and Pages

PO-Aligned

SokzBuraka [Beet Juice] (~840,000 followers) — a left-leaning “satirical” Page that shares memes and content mocking PiS. Has been accused of spreading misinformation.

Racjonalna Polska [Rational Poland] (~279,000 followers) — anti-PiS Facebook Page with the goal of “normalizing Polish politics and supporting rational and moderate political initiatives.” Posts memes and other content mocking PiS.

PiS-aligned

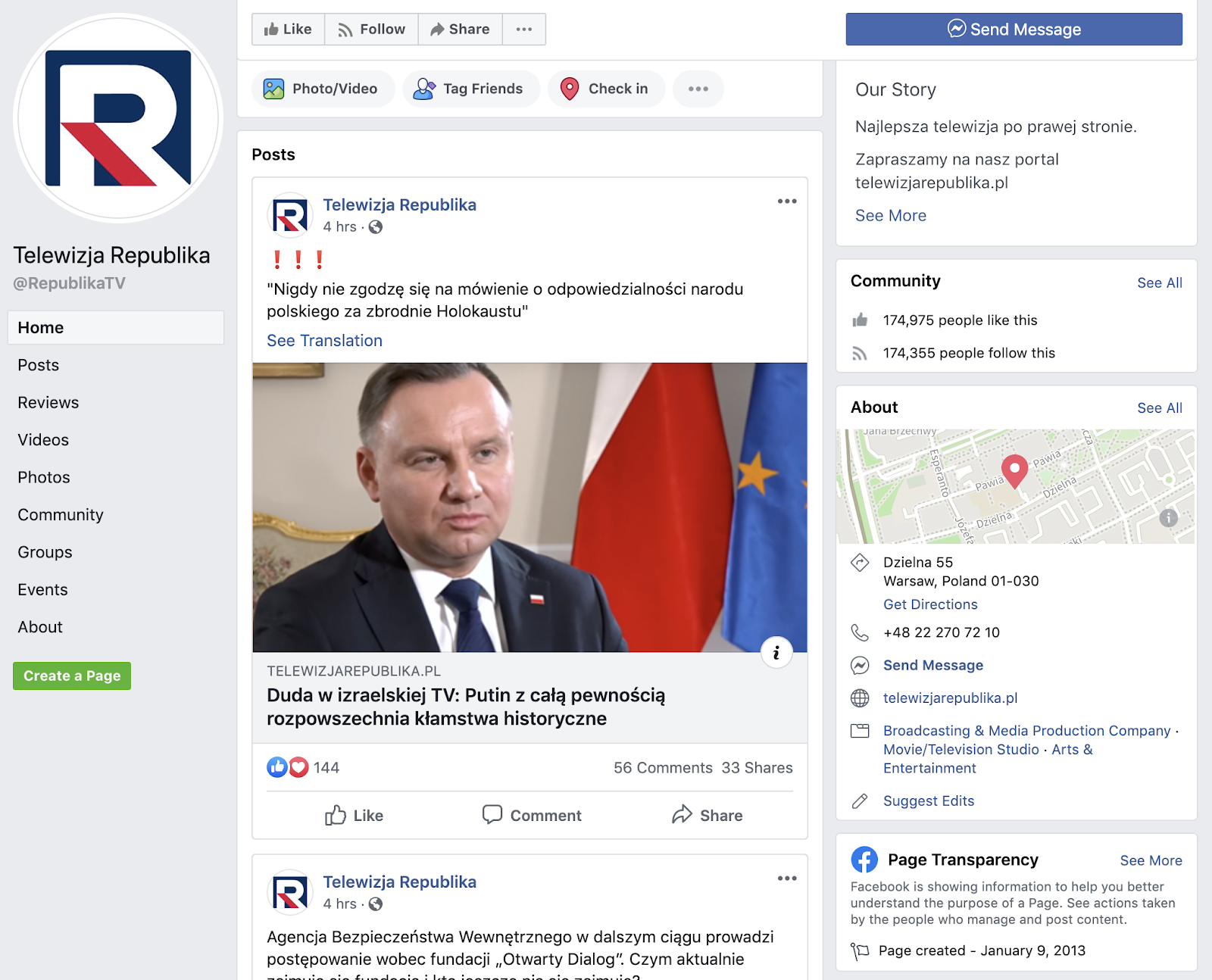

Telewizja Republika [Television Republic] (~175,000 followers) — ”the best television on the right.” Pro-PiS Page with a strong pro-Church slant.

Polska Prawa i Sprawiedliwa [A Just and Right Poland] (~20,000 members) — pro-PiS Group that posts anti-opposition memes.

Far-Right

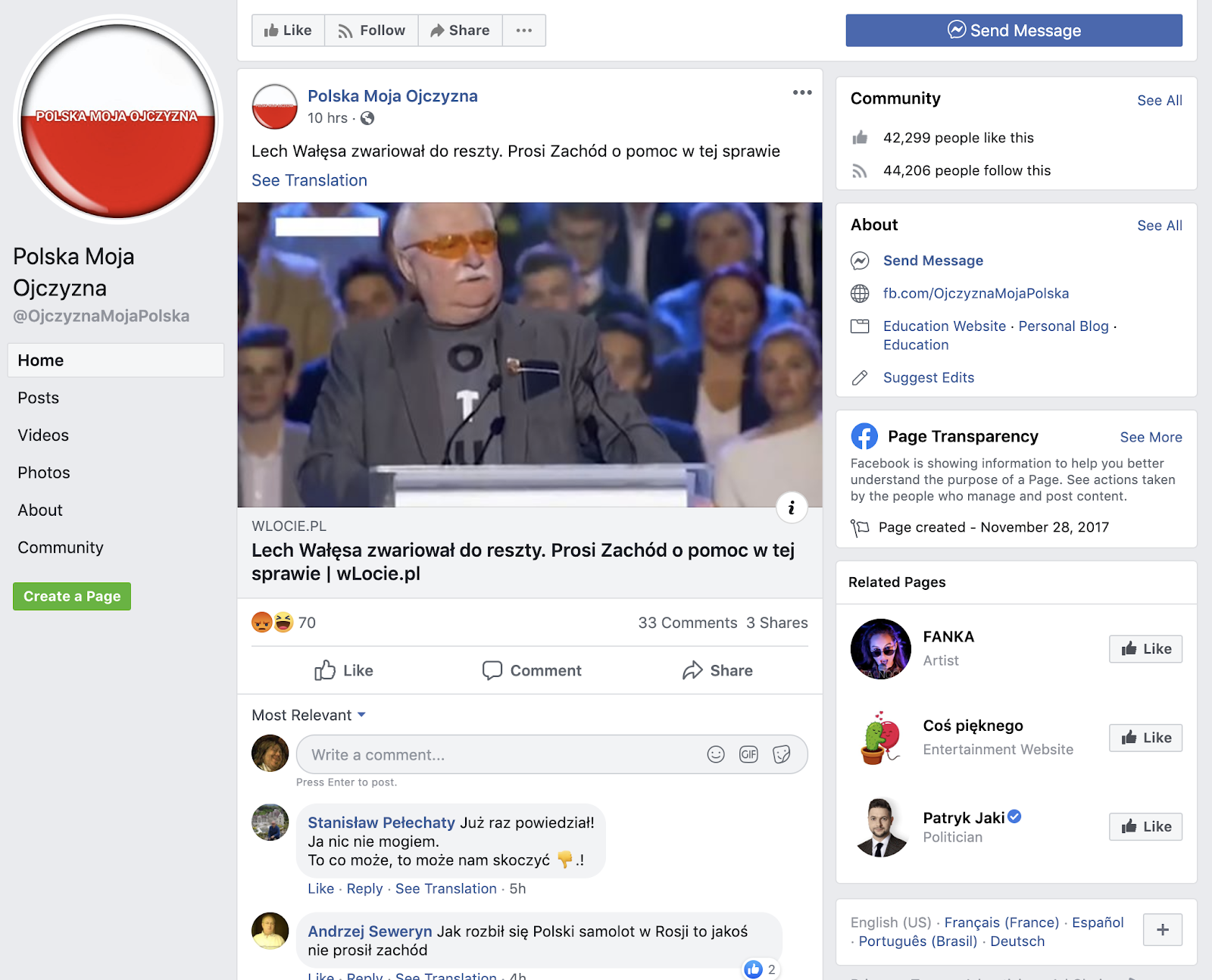

Polska Moja Ojczyzna [Poland My Homeland] (~44,000 followers) — far-right Page that shares news and memes; frequently posts anti-Semitic content.

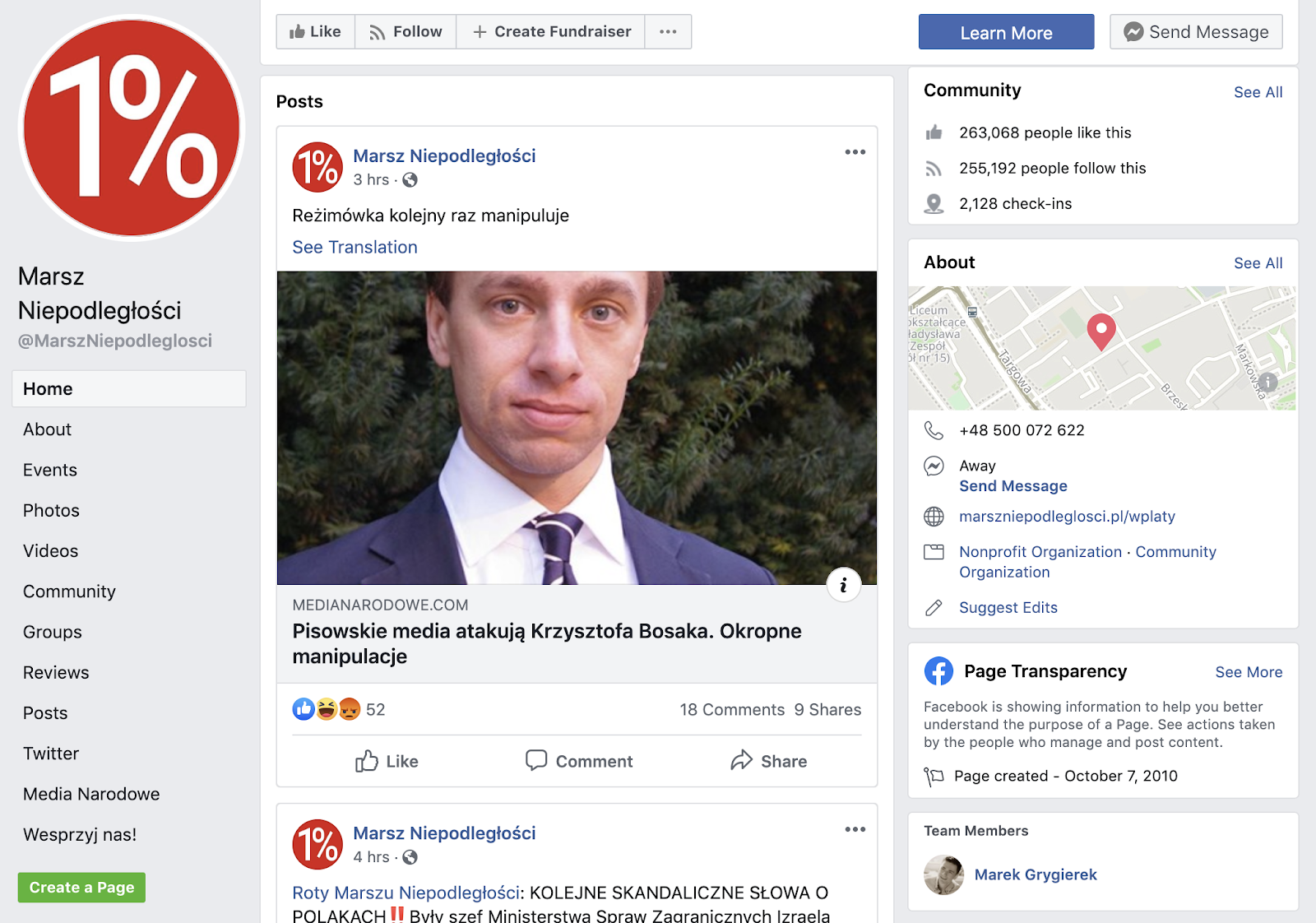

Marsz Niepodległości [March of Independence] (~255,000 followers) — site associated with the far-right movement March of Independence; posts inflammatory and conspiratorial content.

While Twitter remains a “niche” platform in Poland—as of December 2019, it had a market share of only 4.69%—it plays an important role as an ideological battlefield; its popularity among politicians and journalists means that it has a significant role in setting the terms of the news cycle. Some observers argue that PiS did this especially well in 2015. This makes Twitter a target for partisans seeking to inject narratives into mainstream media or alter the terms of a debate, in spite of its relatively small user base in Poland.

Disinformation and Misinformation Threats

The Domestic Arena

Highly polarized societies with high levels of social-media use, like Poland, are generally susceptible to online disinformation campaigns. A report by the Oxford Internet Institute showed that Poland was especially vulnerable to “junk news” shared on Twitter and Facebook in the run-up to the 2019 European Parliament Elections: according to the report, Polish internet users shared more “junk news” than legitimate news on Twitter. Furthermore, reports of disinformation and misinformation used by all sides are on the rise. Opponents of PiS, for example, created and circulated false images showing PiS MEPs carrying crosses in the European Parliament, adding “A strong group of exorcists already at work!”’

A post on the anti-PiS Facebook Page Racjonalna Polska featuring a falsified image. The captions read “Well it’s started” and “A strong group of exorcists already at work!”

Similarly, PO supporters continue to spread allegations that Jarosław Kaczyński signed a loyalty pledge to the Polish Communist Party in the early 1980s, despite the fact that this claim has been debunked. And the popular Facebook account SokZBuraka [“Beet Juice”] (850,000 Page likes)—whose founder Mariusz Kozak-Zagozda was reported to have worked as a promotional representative for Warsaw’s City Hall, currently in the hands of the opposition party—has circulated false claims about PiS politicians, such as the allegation that PiS politicians are profiting from the privatization of tenement houses in Warsaw.

On the other hand, PiS-controlled state media, especially TVP, the largest broadcaster in Poland, have taken to pushing dubious narratives and using misleading images and footage as part of their coverage, which increasingly resembles pro-PiS propaganda. In one case, after young doctors went on strike to protest low wages, TVP showed a young doctor’s pictures from social media and claimed that they were evidence that she had been on exotic vacations; but in reality the pictures were from medical mission trips. TVP has also been accused of manipulating interviews to make opposition politicians look bad and using invented quotes to burnish PiS’s image. And its use of misleading and fabricated evidence is not restricted to Polish politics; like many conservative broadcasters, TVP has gone out of its way to attack George Soros and Greta Thunberg, in one instance by broadcasting a doctored image.

A doctored image of Greta Thunberg shown on PiS-controlled state TV and intended to discredit climate-change activism. The original image features Al Gore, not George Soros.

In general, false or exaggerated claims and fabricated quotes have become a regular part of online campaigning in Poland. It is especially common for content-creators with nationalist agendas to spread dubious and false stories related to anti-immigrant and anti-LGBT narratives. For example, PiS-Chairman Jarosław Kaczynski warned of refugees bringing “various parasites and protozoa” into the country, heating up the immigration debate. Likewise, PiS politicians have echoed numerous false claims about the LGBT movement, including the assertion that “LGBT is a promotion of pedophilia.” As in other EU countries, xenophobia (especially Islamophobia) and homophobia continue to drive misinformation and disinformation traffic on social media.

Polish history and collective memory is another area of contention. PiS has turned to revisionist history to present a more glorious version of Poland's complicated past. Poland’s place in the Holocaust has been a particular focus for PiS, exemplified by a 2018 amendment of the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance (popularly known as the ‘Holocaust Law’) which made it illegal to assert that Poles had a role in the Holocaust and was linked by some observers to Holocaust denial. Simmering nationalist sentiment in Poland and Ukraine has led to renewed tensions over another historical issue, the massacre of Poles by Ukrainian nationalists in the Volhynia in World War II. This issue continues to cloud Ukrainian-Polish relations and has become a rallying point for far-right groups in particular. It has also been a focal point for Russian influence operations, which seek to elevate these far-right groups in order to cause the two countries to quarrel. Indeed, Korwin-Mikke, one of the leaders of the far-right party Konfedracja, has openly adopted the Russian line, arguing that “Russia is now our ally—and Ukraine, the enemy,” a line Russian media have eagerly echoed. In sum, collective memory is very much at the center of Polish politics, especially on social media, and these events are easy targets for actors seeking to sow division or stir up passions.

These are some of the themes that have appeared in disinformation and misinformation campaigns in Poland in the past and are likely to appear again. We include more specific narratives and examples below.

Foreign Threats

Poland’s combative domestic politics make for an information environment laden with misinformation and disinformation; but Poland has also been targeted by foreign influence operations as well—specifically by Russia and Russia-affiliated agents. A report by the Warsaw Institute suggests that, while Poles are resistant to the kind of overt pro-Russian narratives featured on RT and Sputnik, Russia-aligned “patriotic” content that attacks Ukraine, Lithuania, the US, Israel, etc., has had success. The example of Korwin-Mikke given above shows just one of the avenues such a narrative might open up. Since the primary goal of this content is to heighten tensions and increase distrust, it can appear to be pro-PiS or anti-PiS; it is especially common for Russia-aligned outlets to attack PiS from the right. The Warsaw Institute’s report shows that pro-Russia narratives can work their way into Polish media in much the same way described in the Internet Observatory’s recent paper on GRU online operations: at the heart of Russia-aligned networks are more or less overtly pro-Russian sites, which, by sharing content on Facebook and Twitter, insert narratives into fringe outlets, spreading the content to even more Polish internet users and potentially even drawing the attention of the mainstream media to the claims, which by this time have been effectively laundered.

Another potential vector for influence in Polish politics comes from the American Christian and far-right organizations seeking to swing European politics to the right, including Steve Bannon’s group, known as The Movement. These organizations have funneled millions of dollars into European politics in recent years, and Poland is a battleground for them. While PiS has made it clear that it does not see Bannon as a partner, other Polish right-wing groups have cultivated connections with influential American far-right figures. Polish electoral laws make it difficult for foreign organizations like Bannon’s to provide money to Polish political parties legally, but the fragmentation of the Polish information environment makes it more feasible to exert influence using other means (see below).

This said, the prevalence of disinformation and misinformation in Polish politics has been largely a domestic problem in the past decade; Poles do not need to look to outside powers to find examples of political agents abusing the possibilities of social media and the internet to spread falsehoods. For this reason, much of our monitoring in the run-up to the election will focus on the domestic actors listed below.

Troll Farms and Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior

The spread of dubious information is not the only kind of online behavior poised to disrupt Polish politics; like most societies with heavy social-media use, Poland has seen the rise of coordinated trolling—specifically, “ePR” firms that flood social media with comments or posts in support of or in opposition to an issue or political figure. These posts and the “conviction” behind them are designed to look authentic but are actually concocted in the manner of traditional PR measures. For example, the PiS-appointed Deputy Justice Minister Łukasz Piebiak was forced to resign in August 2019 after it was revealed that he had coordinated an online harassment campaign directed at judges who were critical of PiS’s changes to the judiciary. Even before this scandal, known as the “Hater Affair” or “Hate Speech Affair” [“afera hejterska”] PiS’s opponents had accused it of using troll farms and various forms of astroturfing to bolster its online presence and attack its enemies.

Similarly, investigative journalists have identified other coordinated trolling efforts directed at Polish internet users and networks of Facebook Pages that engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB)—specifically to boost far-right candidates and spread false stories with anti-LGBT, anti-immigrant, and anti-Semitic content. In 2019 the activist collective Avaaz uncovered a large network of Poland-based Facebook Pages (subsequently taken down) that used CIB to gain over 8 million followers. Investigators for VSquare, in turn, found that this network was connected to PiS’s Adam Andruszkiewicz and Confederation’s Janusz Korwin-Mikke. These Pages relied on a few tactics to gain followers: they posted the same (usually fabricated) story simultaneously on multiple Pages, reposted the same content many times, always as “breaking news,” and frequently changed their names. Another VSquare investigation found that Cat@Net, a supposed “ePR agency,” was running 179 fake Twitter and Facebook accounts and had signed contracts with entities on the left and the right to burnish their online image. Finally, Politico recently traced the right-wing supposedly French website France Libre 24 back to Polish far-right activists seeking to boost their French ideological allies—in this case, too, Korwin-Mikke has been implicated.

These investigations make it clear that the infrastructure and wherewithal for such activities are in place in Poland, and it is possible that they will be employed in the coming months, both by domestic actors with partisan objectives and by foreign entities seeking to influence the election.

Relevant Actors

Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [PiS] (right-wing populist, incumbent)

Andrzej Duda — current President, candidate from PiS

Jarosław Kaczyński — chairman of PiS

Mateusz Morawiecki — Prime Minister of Poland

Beata Szydło — MEP, former Prime Minister of Poland

Platforma Obywatelska [PO]/Koalicja Obywatelska [KO] (Centrist, liberal-conservative, primary opposition coalition)

Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska — presidential candidate from PO

Grzegorz Schetyna — former chairman of PO

Donald Tusk — founder of PO, former president of the European Council

Borys Budka - chairman of PO

Other Candidates and Parties

Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz — presidential candidate from the Polish People’s Party [ludowcy], a liberal-conservative party to the right of PO.

Robert Biedroń — presidential candidate from The Left [Lewica], a center-left political alliance.

Szymon Hołownia — independent centrist presidential candidate and former television host.

Krzysztof Bosak — presidential candidate from Confederation Liberty and Independence [Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość], a far-right party. Previously involved in All-Polish Youth and the National Movement, both far-right movements.

Other Domestic Actors

Far-right parties (All-Polish youth, National Radical Camp, National Revival of Poland, et al.) — these parties will likely support the candidate from Confederation Liberty and Independence, or, failing that, seek to pull Duda (the current president) and PiS to the right, particularly on foreign-policy issues (Ukraine, Germany, and Russia) and a handful of domestic issues (immigration, LGBT rights, abortion). The extreme far right will likely push for further alienation from the EU (“Polexit”) and make an issue of the status of Polish minorities in the Baltics, Belarus, and Ukraine. In the run-up to the 2019 European Parliament elections, far-right Facebook Pages tended to attack PiS in favor of Confederation Korwin (a predecessor to Confederation Liberty and Independence.)

Leftist parties (Lewica Razem, et al.) — these groups will push for better relations with Brussels and a Poland that is more integrated with the EU and less closely tied to the US. (In part because of its Communist past, Poland does not have significant far-left political movements.)

Religious organizations — The Catholic Church and Radio Maryja both have a significant impact on elevating certain governmental/nationalist narratives. Ordo Iuris, a fundamentalist Christian think tank with close ties to PiS, is also influential.

International Actors

Russia — a history of hundreds of years of enmity makes Poland-Russia relations very complex and generally hostile, with periods of detente. Russia’s increasing bellicosity in Eastern Europe affects Poland directly. Though it has not been invaded and had its territory annexed, like Ukraine, its neighbor to the east, it has been steadily targeted by influence operations (see above) and cyber attacks originating in Russia.

USA — While the US and Polish governments remain close allies, far-right and Christian groups in the US have sought to boost ideological allies in Poland (see above).

Ukraine — traditionally friendly relations have been marred by resurfacing strife over atrocities committed during WW2, including the Volhynia massacre, and an influx of Ukrainian workers has led to xenophobic tensions. PiS’s position on Ukraine-related issues is ambiguous, as it moved to declare the massacre a genocide, while it has simultaneously overseen a large increase in the number of Ukrainian workers in the country.

Belarus — After a long period of essentially static relations between Poland and Belarus, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has caused them to seek closer ties. Both countries are home to populations of the other’s ethnic group.

Germany — PiS has made antagonism towards Germany (seen in particular as the embodiment of the EU) part of its platform, undermining bilateral relations that had been unprecedentedly positive.

Visegrad Group (Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia) — attempting to build a coalition within the EU against the Germany-France center and Russia’s interference in the former Warsaw Pact states.

Key Narratives in Play

Below we describe some of the issues that could be leveraged in malign narratives. The narratives below are far from the only ones we will investigate, but they are topics of debate in Polish society that may be leveraged by inauthentic actors:

- LGBT Issues: PiS has made LGBT rights a campaign issue; a specific point of tension is the establishment of “LGBT-free zones” in certain Polish cities.

An anti-LGBT post on an All-Polish Youth Facebook Page. “Wherever there is a member of All-Polish Youth, there is already a LGBT-free zone!” the caption reads.

Feminism and Women’s Rights: in 2016 PiS has attempted to outlaw abortion entirely, triggering large protests (known as the “Black Protest” [czarny protest]). This led to an uneasy status quo, and abortion is still a frequent topic on social media.

Immigration: PiS made opposition to immigration a large part of its program in 2015 (focusing on immigrants from the Near East). Now anti-immigration groups have shifted their focus to Ukrainians, who make up the majority of immigrants to Poland. This issue dovetails with the conflict between Ukrainian and Polish nationalists (see below).

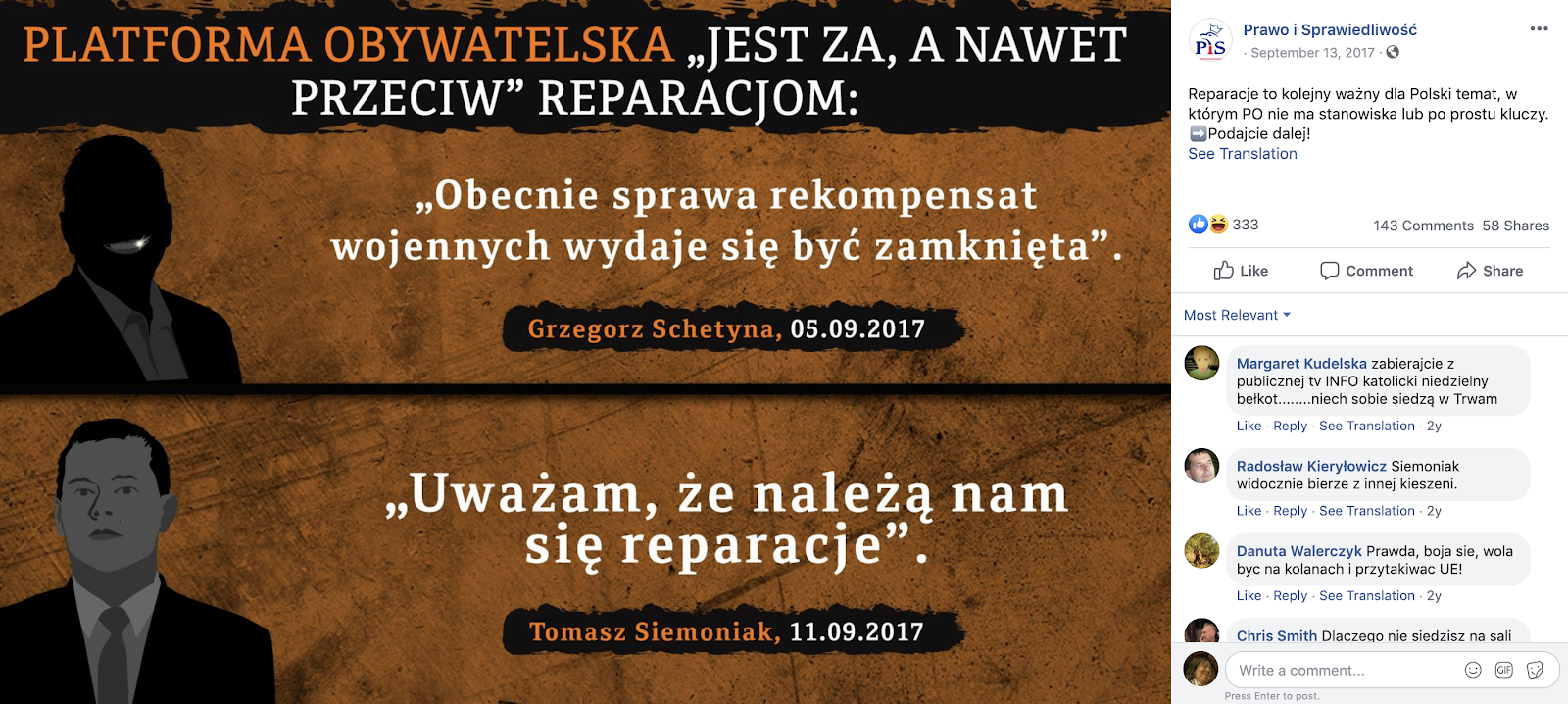

WW2 and the Holocaust: Polish society is still riven by the events of 1939-1945, and arguments about Poland’s role in and relationship to the Holocaust are very common. The topic of reparations has become a focus on the right, in particular. Far-right groups demand reparation payments from Germany but reject the notion that such reparations are owed to Polish Jews as well.

A post on PiS’s Facebook Page calling for reparations from Germany.

Corruption: Corruption scandals have roiled both sides of the political spectrum and been the basis for attacks.

Energy Policy and Nord-Stream 2: the Russian pipeline (supported by Germany) has been a point of contention in Poland, which is dependent on energy imports.

US-Poland Relations: the US maintains thousands of troops in Poland, and groups on the left and the right attack the centrist parties for their dependence on the US (albeit for different reasons). Another important issue is the elimination of visa requirements for Poles, which was seen as a major coup for PiS.

Judges and Judicial Independence: PiS’s attempts to reconfigure the Polish judicial system have drawn fierce criticism from the EU and its opponents in Poland.

A post on the Rational Poland Facebook Page calling on Poles to resist PiS’s changes to the court system.

Environmental Issues: While Poland remains dependent on coal, a burgeoning climate-activism movement makes the case for joining other EU countries in addressing climate change—adding to an already fraught political debate over Poland's position in the EU.

Relations with Ukraine: Ukrainian and Polish nationalists have clashed over the status of the massacre of Poles by Ukrainians in Volhynia during WW2, and an influx of Ukrainian immigrants has aggravated these tensions. This has been a useful issue for Russian influence operations, which seek to divide Poland and Ukraine.

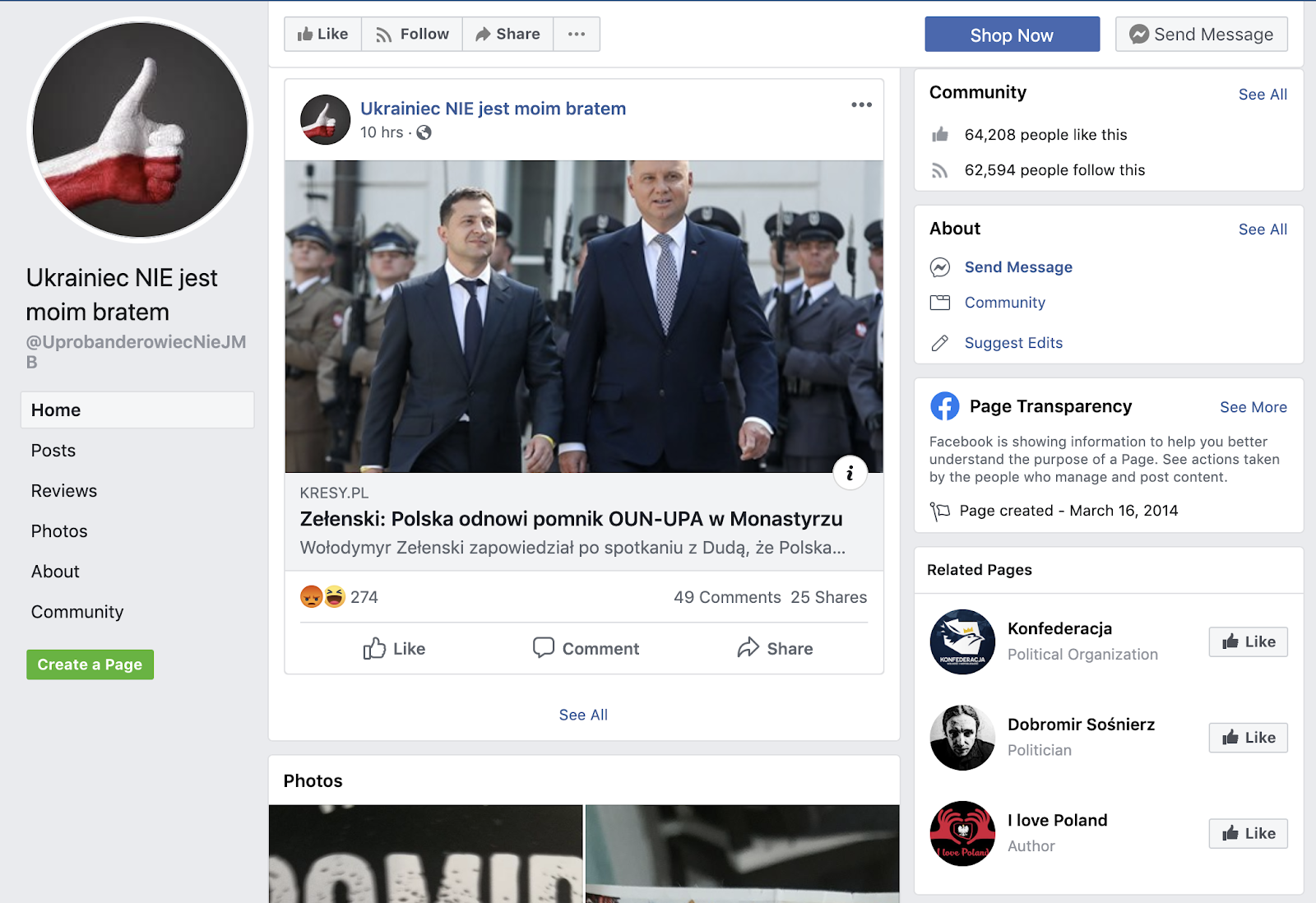

A far-right Facebook Page called “A Ukrainian is NOT my brother.”

Pan-Slavism: Interestingly, another issue popular among nationalists takes the opposite view: that all Slavic peoples (including Ukraine) should unite in opposition to American and Western-European influence. This issue is also useful for Russia-aligned actors.

For Further Reading

Disinformation Assessments

Computational Propaganda in Poland: False Amplifiers and the Digital Public Sphere, Robert Gorwa, Oxford Internet Institute.

The Weaponization of Culture: Kremlin’s Traditional Agenda and the Export of Values to Central Europe, Péter Krekó, et al., Political Capital Institute.

Far Right Networks of Deception, Avaaz.

European Elections in the V4: From Disinformation Campaigns to Narrative Amplification, Miroslava Sawiris, et al., Globsec.

Today’s Potemkin Village: Kremlin Disinformation and Propaganda in Poland, Małgorzata Zawadzka, Warsaw Institute.

Polskie fejki, rosyjska dezinformacja. OKO.press tropi tych, którzy je produkują. Niektórzy z nich nie istnieją, Patryk Szczepaniak and Konrad Szczygieł, Oko.press.

Junk News During the EU Parliamentary Elections: Lessons from a Seven-Language Study of Twitter and Facebook, Nahema Marchal, et al., Oxford Internet Institute.

Information Warfare in the Internet: Countering Pro-Kremlin Disinformation in the CEE Countries, Antoni Wierzejski, et al., Centre for International Relations.

Media Analysis

Pluralism Under Attack: The Assault on Press Freedom in Poland, Annabelle Chapman, Freedom House.

Media w Polsce. Do kogo należy prasa, telewizja, portale czy radio?, money.pl.

Political Analysis

Revealed: dozens of European politicians linked to US ‘incubator for extremism’, Nandini Archer and Claire Provost, Open Democracy.

Divided at the Centre: Germany, Poland, and the Troubles of the Trump Era, Piotr Buras and Josef Janning, European Council on Foreign Relations.

Poland’s Historical Revisionism Is Pushing It Into Moscow’s Arms, Mateusz Mazzini, Foreign Policy.

Hostile Takeover: How Law and Justice Captured Poland's Courts, Christian Davies, Freedome House.

Poland 2020: A Crunch Year for Populists' Grip on Power, Claudio Ciobanu, Balkan Insight.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anna Gielewska and Agata Foryciarz for their helpful feedback and suggestions in preparing this report.