On March 11, 2020 Twitter shared with the Stanford Internet Observatory accounts and tweets associated with five distinct takedowns. These include:

- Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt: 5,350 accounts and 36,523,977 tweets. The removed accounts were linked both to a September 2019 takedown of accounts linked to DotDev, a digital marketing firm operating out of Egypt and the UAE, and a December 2019 takedown attributed to Smaat, a Saudi Arabian digital marketing firm. This takedown was a result of a tip the Stanford Internet Observatory shared with Twitter in December 2019.

- Facebook also shared with the Internet Observatory 55 Pages that are linked to this operation; these Pages were run out of Egypt. Facebook attributes these Pages to Maat, a social media marketing firm.

- Egypt (El Fagr newspaper): 2,541 accounts and 7,935,267 tweets. A takedown of accounts tied to the El Fagr newspaper, an Egyptian weekly tabloid. The removed accounts were linked to an October 2019 takedown of El Fagr’s activities by Facebook.

- Honduras: 3,104 accounts and 1,165,019 tweets. A takedown of accounts linked to a staffer of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández.

- Serbia: 8,558 accounts and 43,067,074 tweets. A takedown of accounts linked to the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), the party of current President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić. These accounts engaged in inauthentic coordinated activity to promote SNS and Vučić, to attack their political opponents, and to amplify content from news outlets favorable to them.

- Indonesia: 795 accounts and 2,700,296 tweets.

In this post we summarize our analysis of the first four operations. We have also written in-depth whitepapers on the Saudi Arabia/UAE/Egypt, Honduras, Serbia, and Egypt and El Fagr operations, linked at the top of the page.

The Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt operation

[FULL REPORT]

In December 2019 the Stanford Internet Observatory alerted Twitter to the hashtag #السراج_خائن_ليبيا (Sarraj the traitor of Libya), a reference to the Libyan Prime Minister’s signing of a maritime agreement with Turkey that angered many regional actors. The hashtag had a suspicious distribution pattern, and was shared alongside infographics linked to an earlier Twitter takedown attributed to digital marketers DotDev. Twitter’s subsequent investigation of this hashtag revealed not just a link between this new network and DotDev, but also a link to Smaat, a Saudi Arabian digital marketing firm that Twitter suspended in December 2019 (SIO’s report on Smaat is here); Twitter believes multiple social media management firms created the accounts in this network. In April 2020 they removed 5,350 accounts, which are the subject of this assessment.

Early appearances of the “Sarraj the Traitor of Libya” hashtag.

On March 25 Facebook shared 55 Pages linked to this network.

Key takeaways from the Saudia Arabia/UAE/Egypt datasets:

- Tweets supportive of Khalifa Haftar - a Libyan strongman who heads the self-styled Libyan National Army - began in 2013. This suggests Saudi Arabia/UAE/Egypt disinformation operations on Twitter targeting Libya began earlier than previously known.

- Accounts claimed to be located in a variety of Middle East and North African countries, with many claiming Sudan. They discussed domestic politics with an anti-Turkey, anti-Qatar, and anti-Iran slant. These countries are geopolitical rivals of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt.

- Recent posts on the Facebook Pages leveraged the COVID-19 pandemic to push these narratives.

- Many of the accounts tweeted links from a set of domains that purport to be news sites for countries like Algeria and Iran; these sites were all created on the same day and publish content with a similar anti-Qatar, -Turkey, and -Iran slant.

- Prominent narratives included discrediting recent Libyan peace talks, criticizing the Syrian government, criticizing Iranian influence in Iraq, praising the Mauritanian government, and criticism of Huthi rebels in Yemen. (We discuss these in detail in our whitepaper)

- There were several interesting behavioral tactics observed in this Twitter data set:

- Hashtag laundering: A geopolitically aligned news website and YouTube channel ran stories about the DotDev-initiated hashtag, with the intent of making it seem like Libyans were (for example) so hostile to Turkey that an anti-Turkey hashtag was trending in Libya. This coverage was grossly exaggerated; the hashtags did not go viral, and the accounts whose tweets they embedded in their articles were subsequently taken down by Twitter.

- Jingoistic personas: The accounts were exceedingly and passionately patriotic to the point of being comedic caricatures. Their profiles emphasized their pride in their purported country, saying things like (translated) “Emirati and Proud” or “Tunisia is my passion” or “I love you, Sudan.”

A March 24, 2020 post from the now-suspended facebook.com/GulfKnights1 criticizing Qatar in the context of COVID-19.

The Egypt operation

[FULL REPORT]

This takedown was attributed to actors linked to the El Fagr newspaper in Egypt. El Fagr has previously been associated with influence operations, possibly on behalf of the Egyptian government, on Facebook and Instagram, which took down a network related to their activity in October 2019.

As with several past influence operations attributed to networks operating out of Egypt (and Saudi Arabia), the content consisted of a mix of auto-generated tweets from religious apps, commercial content, geopolitical news content, as well as subversive political astroturfing pushed by accounts that appear to be personas. The political astroturf identities were often made and deployed for a specific topic, created within a short time period and immediately deployed towards a particular topic with very little additional content.

Key takeaways:

- The topics in this Egypt-attributed data set had high overlap with topics in past Egypt-attributed takedowns: negative content about regional rivals such as Qatar and Iran, positive tone towards the Egyptian government.

- News properties were at the center of this network. Several appeared to be legitimate organizations, such as El Fagr itself, and other outlets based in UAE and Yemen.

- Other handles that appeared to be news outlets were fabricated properties that had Twitter accounts with “news” in the name, but did not appear to be actual news outlets - there were no signs of original content. Additionally, a few used names that tried to create the perception that they were regional affiliates of legitimate news organizations (ie, @Foxnewseurope_f).

- Fabricated personalities were created in batches, some serving as content creators, and others serving as content amplifiers. The creators would tweet “original” messages nearly simultaneously (3-6 accounts would put out the same text but not engage with each other), and then outer networks of “disseminators” would amplify them all.

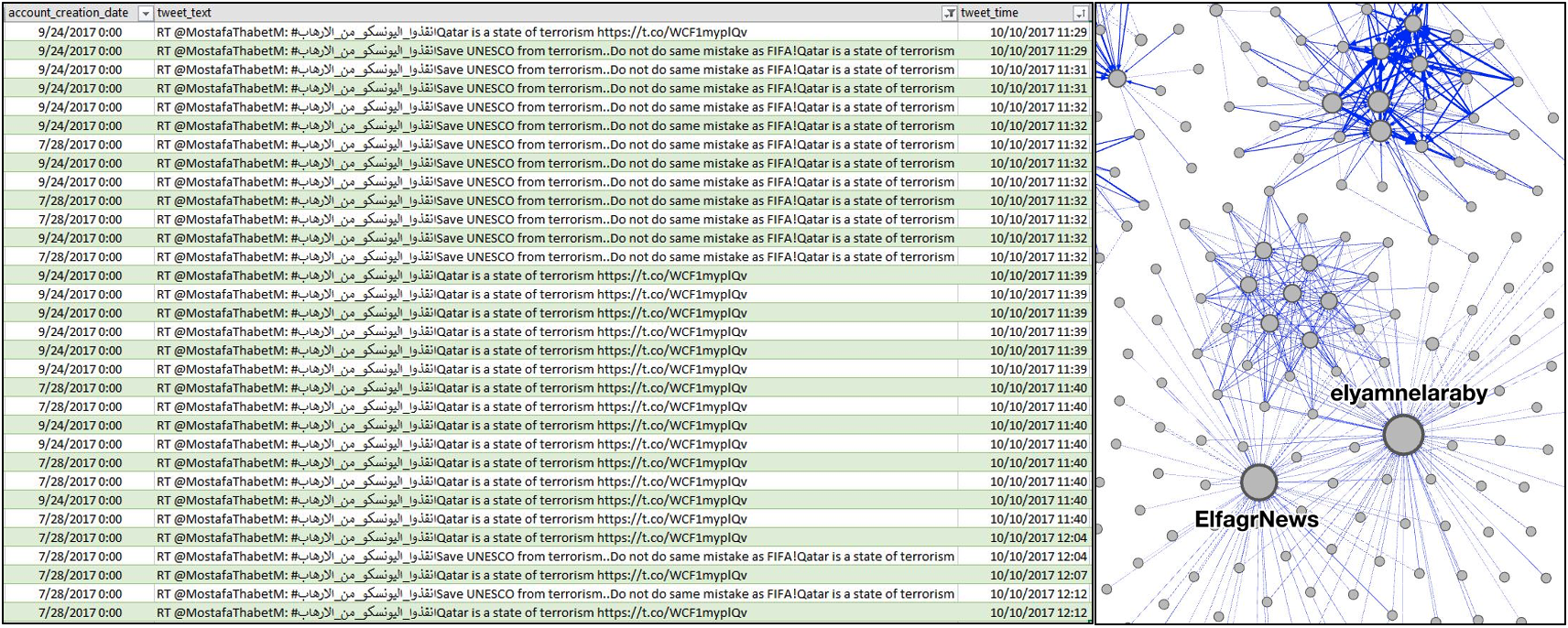

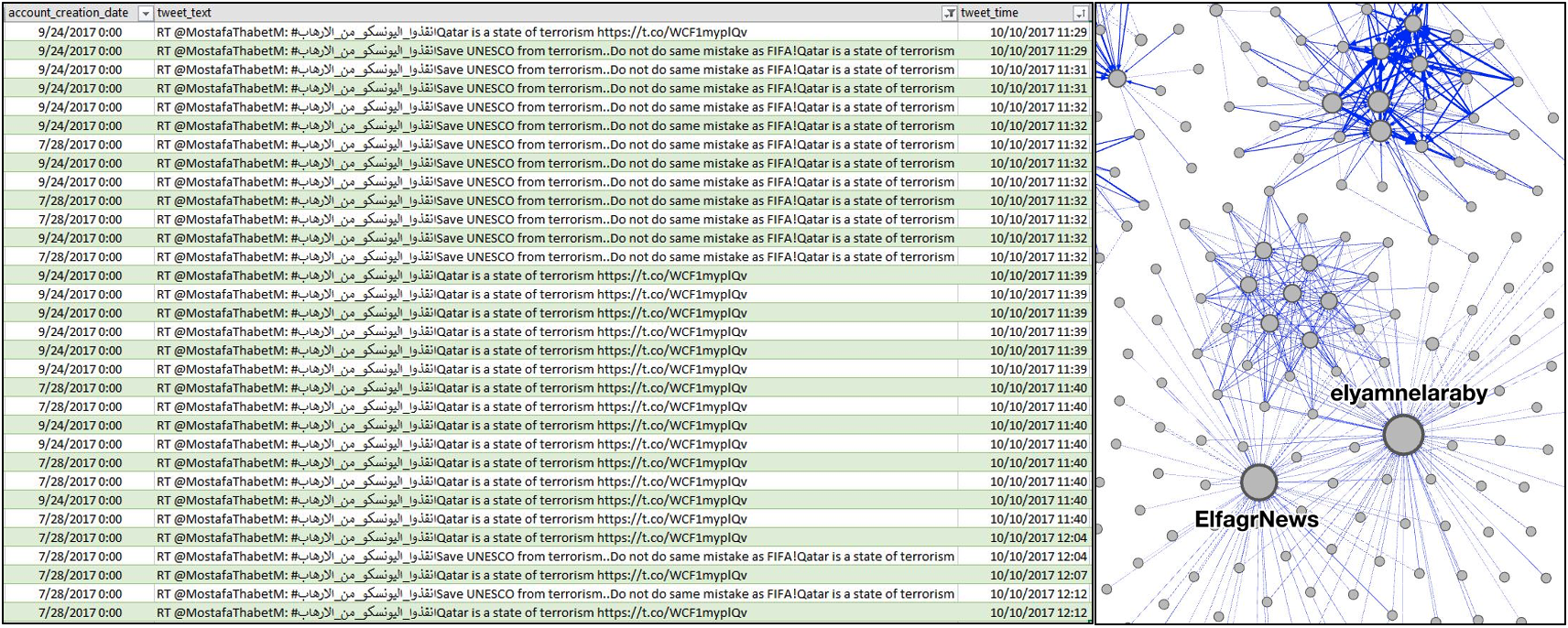

- There was significant amplification of El Fagr’s editor, @MustafaThabetM, with over a hundred thousand retweets - not only from the paper’s own twitter handle, but from a collection of persona accounts. The retweeted content often included sensational or highly political hashtags related to Qatar.

An example of one of the many instances in which networks of accounts created in batches were used to amplify El Fagr’s editor, Mostafa Thabet.

The Honduras operation

[FULL REPORT]

This takedown of over 3,000 accounts was attributed to the administration of the Honduran President. and is related to a July 25, 2019 Facebook takedown of 181 accounts and 1,488 Pages. Among the accounts pulled down were those of the Honduran government-owned television station Televisión Nacional de Honduras, several content creator accounts, accounts linked to several presidential initiatives, and some “like-for-likes” accounts likely in the follower-building stage. Much of the tweet behavior seems targeted at drowning out negative news about the Honduran president by promoting presidential initiatives and heavily retweeting the president and news outlets favorable to his administration. Interestingly, a subset of accounts in the dataset are related to self-identified artists, writers, feminists and intellectuals who largely posted tweets critical of the Honduran president Juan Orland Hernandez (‘JOH’).

Tweets by date. A coincides with the Honduran constitutional court permitting presidential re-election; B is the period immediately after the 2017 election; C occurs during the trial of Tony Hernández.

Network graph of all retweets in the dataset. The purple cluster centers on the account of honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández; the turquoise cluster surrounds the account of the Honduran President’s communications office; in pink are news accounts, and green represents what we’re calling the “activista” cluster.

Key Takeaways:

- The Honduras takedown consists of 3,104 accounts and 1,165,019 tweets. 553,211 tweets were original and 611,808 were retweets. Accounts dated as far back as 2008, but roughly two thirds were created in the last year.

- The accounts created in the last year appear largely automated. Their activity overwhelmingly involved retweeting Honduran President @JuanOrlandoH. Approximately 37% of the tweets in the dataset mentioned @JuanOrlandoH.

- The largest removed account was that of Televisión Nacional de Honduras (TNH). The government-controlled TV station’s facebook page was also removed in July 2019. TNH has new social media presence on both platforms as of March 25, 2020.

- Some of the removed accounts are associated with known television and media personalities, one of whom, Chano Rivera, is also a political consultant and publicist.

- The frequency of hashtags including (in translation) #TheNewHonduras, #HondurasAdvances, #BetterLife, #HondurasActivates, #ISupportYouJOH, #LongLiveJOH and #HondurasIsProgressing shows widespread promotion of the president’s initiatives within the dataset. Minimal mention is made of some major news events, such as the criminal conviction of the president’s brother, Tony Hernandez, suggesting that the tweets sought to drown out negative press.

- A set of roughly a dozen accounts associated with self proclaimed writers, artists and feminists formed a distinct group in the dataset. These accounts were the only accounts heavily critical of the government. They also interacted less with the dominant media landscape and the president than other accounts in the dataset. There does appear to be evidence of coordinated activity across the cluster.

The Serbia operation

[FULL REPORT]

One of the takedowns announced on April 2, 2020 was a large cluster of Serbian accounts. These accounts were primarily engaged in cheerleading current Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and his allies, in attacking the Serbian opposition, and in artificially boosting the popularity of Vučić-aligned tweets and content. Among other things, the accounts appear to have focused on supporting Vučić’s run for president in 2017 and tamping down public support for the opposition-led protests known as “1 of 5 Million,” which began in late 2018.

One of the most popular accounts in the Serbia-related takedown, @belilav11, replying to a tweet from the Serbian Progressive Party, the party of current Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić: “The government belongs to the people, not to the yellow tycoons [i.e., the opposition] and their mentors from the west. The people decide in the election who will be in power.” Accounts like this one tweeted in support of Vučić and his allies and attacked the Serbian opposition.

Key takeaways

- The network consisted of approximately 8,558 accounts. While many of these accounts existed earlier, most of the network’s activity came in 2018 and 2019. The accounts sent more than 43 million tweets altogether.

- The accounts served as a coordinated pro-Vučić brigade on Twitter. They tweeted constantly in support of Vučić—over 2 million tweets were sent with the hashtags #Vucic and #vucic—and derided his rivals and the “1 in 5 Million” protests.

- The accounts worked steadily to direct Twitter users to pro-Vučić news sources. Among their tweets were over 8.5 million links to sns.org.rs, informer.rs, alor.rs, and pink.rs, the official site of Vučić’s party and three Vučić-aligned news sites, respectively.

- The accounts relied on a few core tactics to boost visibility and achieve their aims:

- Dogpiling onto opposition-related content. Tweets by opposition politicians and publications were swarmed by the accounts, which replied with critical or derisive comments to give the content the appearance of unpopularity.

- Taking over opposition-related hashtags. When protesters popularized the hashtags #1od5miliona and #PočeloJe, the accounts attacked the originators and attempted to co-opt the hashtags with pro-Vučić content.

- Retweeting Vučić-aligned accounts to boost their popularity. The accounts retweeted @avucic 1.7 million times, @sns_srbija (the official account for Vučić’s party) over 4.5 million times, and @InformerNovine (an SNS-aligned newspaper) over 1.8 million times. Many accounts were engaged solely in retweeting @avucic.

While a precise connection between this network and SNS has not been established, there can be no doubt, given the content these accounts shared and the time period in which they were active, that this network was aligned with Vučić’s efforts to entrench himself and his party in power.

The broad spectrum of takedowns in the April 2020 collection serves as a reminder that coordinated inauthentic behavior manifests globally, comes from a range of actor types, is reliant on broadcast media as well as the social media ecosystem, and that determined manipulators regenerate networks and update tactics with regularity.

4/2/2020, 11:30AM PST: THIS POST WAS UPDATED TO INCLUDE ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FROM FACEBOOK