Taiwan Election: Disinformation as a Partisan Issue

On January 11, 2020, Taiwan held its 15th presidential and 10th Legislative Yuan election. Taiwanese citizens soundly re-elected Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) candidate, Tsai Ing-wen, who won 57.1% of the vote over her opponents, Kuomintang (KMT) candidate Han Kuo-yu (who took 38.61%), and the People’s First Party candidate James Soong (4.26%). The DPP also maintained its majority in the Legislative Yuan, though with a slight decrease of a few seats. Voter turnout was high, with almost 74% of eligible voters casting ballots, up from 66% in 2016. According to Liberty Times Net, the number of Taiwanese voters living overseas who registered to vote on Saturday more than doubled from 2016.

In this blog post we provide an overview of some unexpected results from the 2020 election. We examine how the election was perceived on social media, within each candidate’s respective Facebook fan Pages and Groups. We wrap up this election coverage series by looking at areas that are important battlegrounds in Taiwan for ongoing disinformation dissemination, such as YouTube, and on the role the perceived threat of foreign interference played in this election. Lastly, we end by focusing on why collaboration to detect and mitigate influence operations is so important.

Presidential and Legislative Yuan Election Surprises

This election set a few historical precedents both for Tsai and for the presidential election process. According to the New York Times, Tsai received more votes and a wider margin of victory than in 2016. Tsai also received more votes than “ever recorded for any candidate in a presidential election in Taiwan” as reported by Focus Taiwan, the English section of the Central News Agency. This result was a dramatic turnaround given her approval ratings at the beginning of 2019. Experts assessed the Hong Kong protests to have been a significant factor – if not the largest factor – in helping Tsai regain her support.

Out of 113 seats, the DPP maintained its majority but dropped from 68 to 61 seats. The KMT gained 3 seats to increase its total to 38. Taiwan’s People Party (TPP), the party of Taipei’s mayor, received a good portion of the votes, winning 5 seats but just 1.5 million votes compared to 4.8 million and 4.7 million won by the DPP and KMT respectively. The remaining 9 seats went to various other parties.

Some results in the Legislative Yuan races came as a surprise. One headline from Focus Taiwan read, “Young candidates, underdogs prevail in several legislative races”. One contested race was between Bo-Wei Chen (陳柏惟) of the Taiwan Statebuilding Party, and incumbent Yen Kuan-heng (顏寬恆) of the KMT. Chen, who was supported by the DPP, defeated Yen in a close race claiming 51.15% of the vote to Yen’s 48.85%. This result was something of a shock, since the KMT candidate came from the Yen family, which has governed the district for more than a decade and is described as a “local political dynasty” by Focus Taiwan. Another surprise victory was Saidai Tarovecahe (伍麗華), who became the first member of the DPP to represent the Highland Aborigine Constituency. Taiwan’s indigenous population in the Lowland and Highland Aborigine districts have historically been represented by legislators from the KMT, KMT-allied splinter party, or independents. Lastly, the third surprise was DPP candidate Lai Pin Yu, in the New Taipei City 12 District. Lai was the youngest legislative candidate in the election at 27 years old, and narrowly defeated the KMT opponent.

Social Media Perception of the Election

On social media, DPP supporters celebrated their candidates’ victory and expressed pride in having Tsai Ing-wen as their president for another term. Several Groups and Pages shared an emotional thank you speech by defeated Legislative Yuan DPP candidate Enoch Wu to his supporters. One user shared a picture of Enoch Wu doing a deep bow to thank his supporters, a very polite gesture, commenting, “this is a real man.” Other users posted content ridiculing statements Han Kuo-yu supporters had made pre-election, such as one supporter’s declaration he would commit suicide if Han Kuo-yu did not win the election, or another supporter’s statement that he would invite all Taiwanese people to fried chicken if Tsai Ing-wen won over 8 Million votes, saying “All of Taiwan can eat fried chicken!”

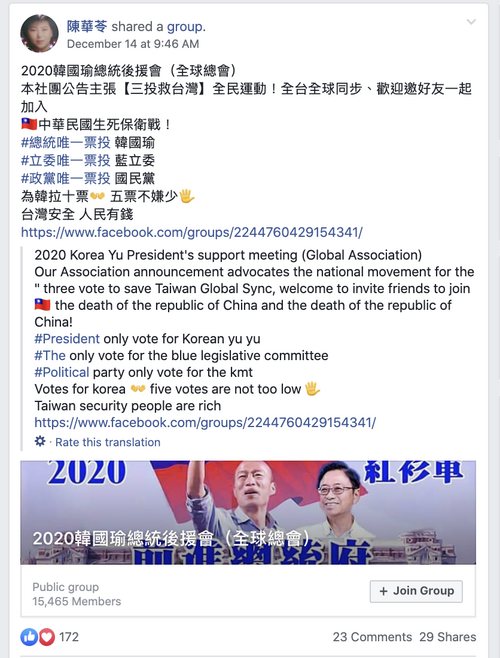

Groups of Han Kuo-yu supporters reacted to their candidate’s defeat in various ways. First, several groups renamed themselves, such as 2024韓國瑜總統後援會(全球總會) (previously 2020韓國瑜總統後援會(全球總會)) changing their 2020 support for Han Kuo-yu for president to support for Han Kuo-yu in the 2024 presidential election. Other groups added the phrase “mayor” or “city government” to their name, or changed the term “president” (總統) to “mayor” (市長).

Examples for name changes; Left: Group replaces “president” (總統) with “mayor” (市長), Right: Group changes 2020 to 2024.

Examples for name changes; Left: Group replaces “president” (總統) with “mayor” (市長), Right: Group changes 2020 to 2024.

Examples for name changes: Group changes 2020 to 2024.

In groups and across pro-Han Kuo-yu/pro-KMT pages, fans expressed feeling sad or depressed about the election result, saying that their “heart hurts” and writing in one post, "Mayor Han you don't need to apologize to the Taiwanese people, the Taiwanese people need to apologize to you!" Others claimed to be bullied by DPP supporters, sharing a video of a Kaohsiung middle school student using a Han Kuo-yu doll to wipe a chalkboard, saying that such poor behavior represented the overall “demeanor of the green people” (green being the color of the DPP). In one popular post, a user protested “Green Terror” and stated “Taiwan was not saved.” Lastly, a post that received 7,000 likes and 1.4 thousand comments complained about allegations against China-friendly news outlets such as China Times. The post asked Han supporters if, should the pro-China outlets be shut down, they would stand up and defend their rights to watch such content.

One post in pro-Han Kuo-yu group 2024韓國瑜總統後援會(全球總會)asks group members if they would be willing to stand up to defend their viewing rights if outlets such as China Times were cancelled due to their support for Han Kuo-yu.

Additional battlegrounds - YouTube

While Taiwan’s election is over and there was no interference attributed to Beijing, a statement from Chinese officials on Sunday reflected continued tension: “No matter what changes there are to the internal situation in Taiwan, the basic fact that there is only one China in the world and Taiwan is part of China will not change.” To that effect, Taiwan is concerned about ongoing attempts by an external force to spread disinformation and control the narrative online. One battleground that appears to be of increasing concern as a potential site for creating and sharing false information is YouTube. A recent article by TechCrunch highlights that over the past two years, YouTube has risen as a “potent” way to spread disinformation in Taiwan. Several researchers in Taiwan have raised this concern, including before the election.

In a letter to the editor published November 2019 in Liberty Times Net and quoted in English in its sister newspaper, Taipei Times, Wang Tai-li (王泰俐), a professor at National Taiwan University’s Graduate Institute of Journalism, wrote that because Facebook and Twitter have shut down fake accounts originating in the PRC (focused on Hong Kong), platforms such as YouTube have become more of a threat, where the channels can disseminate “false information and plausible images” on a massive scale. While this is not a foregone conclusion - YouTube has also taken down suspicious activity related to Hong Kong - Wang highlights several specific examples to illustrate this concern. One suspicious YouTube channel highlighted by Wang and reviewed by the Taiwanese Bureau of Investigation is 希達說台灣—玉山腳下, translating in English as “Xida speaks on Taiwan - At the foot of Yushan,” where Yushan is the tallest mountain in Taiwan. This channel mainly focused on denouncing Tsai Ing-wen’s government, with one popular video published in September 2019 questioning whether Tsai actually received her PhD from the London School of Economics (LSE). LSE confirmed her degree in a statement in October 2019 in an attempt to dispel the rumor. In October 2019, the Bureau of Investigation revealed that the host of the channel was a Chinese state reporter. Since the Bureau’s announcement, the channel has stopped uploading videos. However, the channel is still up, which means, as Wang argues, that anyone can view the videos without knowing the information is false. Wang’s research discovered 10 similar YouTube channels to “Xida speaks on Taiwan - At the foot of Yushan” that were created from August to October, some of which are still up on YouTube. According to the Taipei Times, Wang’s research finds that some of the channels with more than 10,000 subscribers are content farms run by Chinese nationals and have simplified Chinese subtitles, which are used in the PRC but not in Taiwan.

Our team at SIO noted the presence of YouTube channels with anomalous behavior that became popular sharing content on other platforms during the recent election. Several of these YouTube accounts were created years ago, but only appear to have begun to post videos recently. Several have unusual growth and viewing patterns. One of these YouTube channels, 高雄林小姐 (“Kaohsiung Miss Lin”) was created in December 2011, but only began to post videos in October 2018, one month before the local elections in which Han Kuo-yu was elected as mayor of Kaohsiung. In the first posted video, the speaker says, “I am not a ‘Wumao’” (Wumao is a term commonly used to describe Beijing’s 50 cent army – bots and trolls paid by the PRC government) and then goes on to claim that Tsai Ing-wen, in fact, uses an “online army.”

An example of the YouTube channel “Kaohsiung Miss Lin”’s anomalous spike in subscribers.

Most recently, Google has taken action to address false information on their platforms specifically in Taiwan. Ahead of the 2020 elections, Google published an article on its Taiwan-Official Blog about a recent annual Media Summit in Taiwan where various fact-checking organizations and newsrooms came together to discuss best practices in fact-checking, increasing media literacy, and responses to false information. The summit focused on bringing a host of stakeholders and researchers to one place to share their latest methodologies for fact checking and flagging false information. The objective of this program, the Google News Initiative writes, is to support the media workers and professionals who are bringing “the latest information back to Taiwan’s applications. We also intend to continuously implement more cooperation and exchanges in Taiwan to combat false information.” (translated).

Takeaways from our research

In our Taiwan election scene-setter blog post, we hypothesized about two prongs of influence operations that might be leveraged in Taiwan’s 2020 election. The first was media manipulation: concern that Beijing might facilitate strategic persuasion and inject disinformation narratives into Taiwanese local media. The second type of interference we hypothesized might be present was subversive social influence using fake Pages and accounts, similar to the significant state-backed information operation targeting Hong Kong protestors on Twitter.

Over the past five months, we did not find any cases of disinformation on social media that we believed to be attributable to the PRC. Facebook, while it did a takedown during the campaign, did not attribute those Pages or Groups to outside influence. We did note some suspicious activity, however, most of it appeared to be domestic hyper-partisan fan groups.

On the media front, we observed the spread of Beijing’s propaganda via their persistent control of channels of influence within the media ecosystem. This observation has been echoed by many, including Cedric Alviani, director of the Asia bureau of Reporters Without Borders, who, in a Foreign Policy article published after the election, accused China of “exploiting a weakness” in Taiwan’s media environment. The article described the media environment in Taiwan as “long a hotbed of poor journalistic standards as outlets rush to be first to publish.”

From our monitoring of Facebook Pages and Groups, we noted how key stories, such as that of the disillusioned PRC spy-turned-defector, have been amplified and weaponized on both sides to discredit the other party. Validating the truth of the story is second to the effort of simply making the story serve the political goals of one’s own side This partisanship has resulted in an environment in which people believe or disbelieve a story based on how well it conforms to preconceived biases, and how well it fits the needs of their political tribe.

Hyper-partisanship is detrimental to fighting disinformation. In Foreign Policy, Nick Aspinwall describes a polarizing effect in Taiwanese politics: DPP supporters are fixated on the fear of Chinese influence, while the KMT denounces this fear as overblown. The partisan divide colors the incorporation of all emerging stories - even false ones - in national narratives. Fierce entrenchment minimizes the desire to truly verify allegations of Chinese meddling before these stories are turned into talking points by Taiwanese politicians.

While there does not appear to have been a PRC influence campaign on Facebook, this election was important to observe not just for Taiwan but also to understand what other countries facing possible external influence operations via Beijing might experience. A Freedom House special report from January 2020 found that China has increased its influence abroad. In the same interview with Brian Hioe of New Bloom, Puma Shen (沈伯洋) spoke about the importance of collaboration in detecting Chinese state-sponsored influence, believing that Taiwan’s experience contending with disinformation might be useful for other countries. In sharing his and other researchers’ analysis, Shen says, “our hope is to do this so that we can help other countries resist disinformation attacks from China and the CCP.” This quote from Shen highlights the need for researchers studying disinformation to collaborate with one another - and to raise the bar of evidence and degree of scrutiny - in order to better spot the influence operations that are evolving everyday.